If there is an act that better defines heroism, I have not seen it.

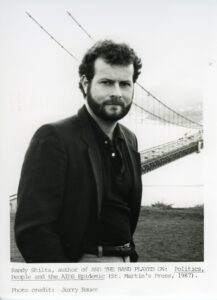

Randy Shilts, paying tribute to those who, while dying from AIDS, agreed to be interviewed for his book, And the Band Played On

After his death, The Beacon News called him “an enormous journalistic talent” whose “ground-breaking work helped frame the national debate about the gay rights movement and AIDS.”

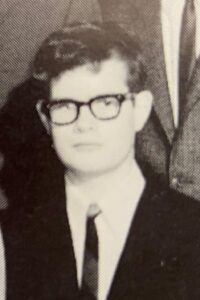

But first, Randy Martin Shilts (1951-1994) was just an Aurora boy growing up at 431 South Calumet Ave. in the quiet, conservative neighborhood that surrounds Aurora University (then Aurora College).

He attended the venerable District 129 neighborhood schools of Freeman Elementary, West Aurora Junior High and West Aurora High School. He had five brothers and a home life complicated by his parents’ infidelity and heavy drinking. His family attended Wesley United Methodist church nearby. Just a boy growing up in Aurora.

Politics was a favorite subject around the Shilts’ kitchen table, and by his early teens Randy was winning essay contests. (“Why I Wish I Could Vote,” sponsored by the Aurora Beacon News) and volunteering for Barry Goldwater.

High School And College Years

Cocky and outspoken, in high school Shilts was a member of the debate team and the National Forensics League, and a contributor to the school newspaper and literary magazine, where he presented his political positions in the clear and self-assured voice that would later earn him so much attention, both good and bad, as a journalist and author.

Cocky and outspoken, in high school Shilts was a member of the debate team and the National Forensics League, and a contributor to the school newspaper and literary magazine, where he presented his political positions in the clear and self-assured voice that would later earn him so much attention, both good and bad, as a journalist and author.

There were few outward signs, early on, of Randy’s gradual acceptance of himself as a homosexual, hardly a surprise given the negative social attitudes of the 1950s and ’60s. although a neighbor recalls that during his school years Randy was generally perceived as “different.”

After graduating from West High in 1969, Shilts attended Aurora College for a year and then headed across country for a degree in journalism from the University of Oregon.

There, his thinking became less conservative and his homosexuality more comfortable. After becoming active in local gay organizations, he found his actual coming out unremarkable.

It was, he said, “an assertion of my dignity as a human being … I’m not ashamed of who I am, and I’m not going to act like I’m ashamed.”

Early Career

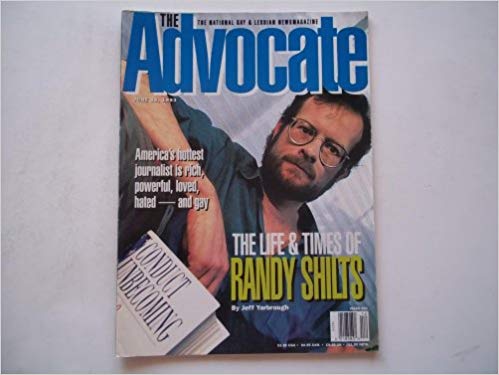

When it was time to begin job hunting, Shilts worked as a stringer and freelancer anyplace he could find work including, rather unpromisingly, at The Advocate, which his biographer Andrew Stoner called a “bar rag” at the time but which is now considered the oldest and largest LGBTQ-interest magazine in the country.

Shilts once commented ruefully that he couldn’t send clippings of his articles home to prove he was making it as a writer because of the nature of the material on the reverse sides.

Shilts added public television to his resume, covering San Francisco politics in the gay community for $75 per story at Station KQED. When funding for the show ran out, Shilts, back in the job market, found his public profile on TV as an openly gay man made it harder than ever to find work.

“Everyone recognized me as a good reporter, but people had never hired an openly gay reporter,” he said.

He cobbled together unemployment checks and the occasional payment for an article and turned to alcohol and drugs as a way to deal with the frustration, troublesome habits that he struggled with for the rest of his life.

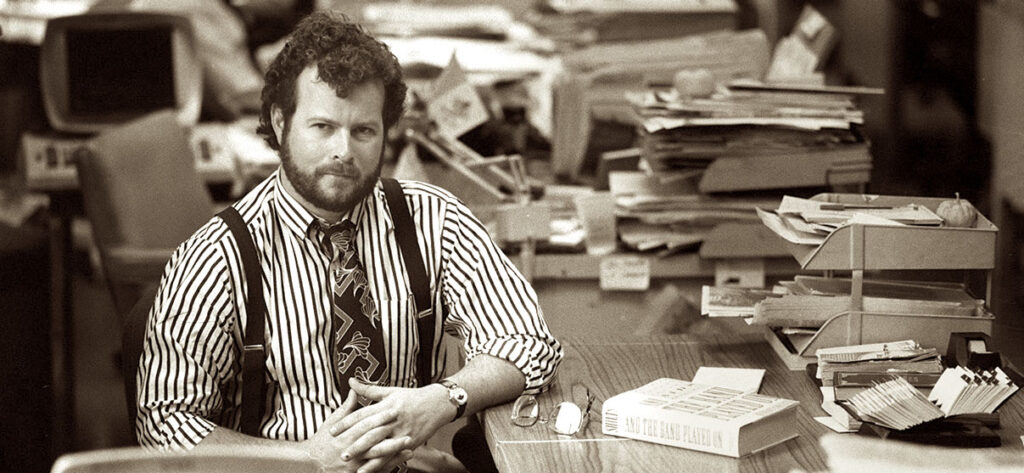

In 1981, Shilts, at age 30, was finally hired by the highly respected San Francisco Chronicle (as its “token fag” said a bath house owner).

“With his striped shirts, flowered ties and suspenders, Randy stood out,” wrote co-worker Susan Sward in SFGate. By her report, he laughed frequently and had a halo of curly blond-brown hair. He was ambitious, lively, talkative, not especially diplomatic and champing at the bit to fight for civil rights and gay liberation.

But 1981 was also when reporting on life as a homosexual took a sudden and dark turn. Shilts was plunged into a phase of his career that was not so much about the issues he was researching for his first book, The Mayor of Castro Street (1982). That book, about San Francisco Board of Supervisors politician Harvey Milk, dealt with hostile politics, coming out, workplace discrimination, violence, public health and a host of other related topics.

Instead, Shilts found himself face to face with the discovery of a terrible new disease, AIDS, and the story that would make him famous as a journalist. It became the second phase of his career.

The Struggle to Report

Mainstream media outlets were not convinced of the newsworthiness of the disease nor did they comprehend that the government’s lack of response was opening the door to an epidemic. Shilts, however, could see far down the road, a characteristic that marked his work all his life.

“The more I found out about AIDS, the more it became clear this was going to be one of the biggest news stories of our generation,” he said.

Shilts began his newsroom struggle to put AIDS on the front page as often as possible.

A dogged investigator and the sort of embedded reporter who could tell all sides of the story, Shilts felt it was imperative to write, not for gays, but for a straight audience. He was convinced that the straight world lived in ignorance of the gay community’s challenges, but could learn if given honest reporting.

Shilts’s work received a mixed reception. A hero to some, he was loathed by others who saw him as a traitor for suggesting that bath houses in San Francisco be shut down as hazards to public health, and that promiscuity played a role in the spread of disease.

He said in the Los Angeles Times, “The gay community didn’t want me to write about things like bathhouses that made gays look bad. But to me that was like going to one side of a burning building and covering the firemen trying to put out the fire, and then ignoring the guy on the other side who’s dumping gas on it.”

Success Story Begins

Shilts’ second book, And the Band Played On (1987), was about AIDS and how the Pandora’s box of the disease was flung open by the inaction, the prejudice and the infighting among scientists at the CDC and NIH, as well as the politics of the Reagan administration.

Shilts’ friend, writer Frank Robinson, said “My god, it was the loudest cry of protest from a gay man at what the national government was doing to its own citizens. For somebody to point the finger at the government and say they were partners in a disease/genocide took a hell of a lot of courage.”

As an aside, there was one scientist who came in for praise in the book: Dr. Anthony Fauci, who Shilts identified as one of the few medical experts concerned enough to call for more government funding for AIDS research.

Fearing that mainstream markets had little taste for the subject, more than a dozen publishing houses turned down the manuscript and, once it was published (by St. Martin’s Press), most major news outlets declined to review it. So it was a surprise to everyone that it spent five weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and movie offers began to pour in.

In 1995, after lengthy tussles over the script and tone, it was made into an HBO movie starring Alan Alda, Ian McKellan, Lily Tomlin, Richard Gere, Phil Collins, Steve Martin and others. It garnered three Emmys. The tide had turned for Shilts, and the fame he had so long desired was on the horizon.

Remembering Aurora

Although by 1987 he was hitting his stride as a national correspondent, a columnist and a best-selling author, Shilts clearly had never left Aurora too far behind him.

In an interview with The Aurora Beacon, he said, “I think being from Aurora, IL, had more of an influence in my point of view than anything. My book (And The Band Played On) is all very West High civics class. Being from the Midwest, you tend to be more straightforward about things. There’s not a lot of b.s. in this book.”

In a series for the Chronicle the same year, he even held the city up as an exemplar of the American mindset, in which people denied the severity of the AIDS problem, thus leading to more deaths.

Many Aurorans were upset by this, and he later wrote a public apology in the Beacon: “I used Aurora only as an example of the kind of place where there’s not many AIDS cases, but still the epidemic is changing lives”.

This gimlet-eyed evaluation of Aurora did not stop Shilts from also writing more generously, if somewhat opaquely, that he learned from the local health department in Aurora that it received so many calls from women’s groups, churches and community organizations wanting to do something to help that they didn’t know what to do with them all.

Then came Shilts’ third journalistic period. As the struggle against AIDS continued, and he continued to report and write opinion pieces, he started another book, this one about the treatment of gays in the U.S. military, taking a deep dive into the long history of discrimination in the armed forces and producing Conduct Unbecoming (1993).

Becoming Famous

By this time, Shilts was famous and The Advocate, now a respected magazine, did a cover story on him, trumpeting “America’s hottest journalist is rich, powerful, loved, hated – and gay.”

Film director Roger Spottiswoode distilled both the fine wine and the vinegar of Shilts’ character and personality when he said Shilts knew he could not prejudge the future so his only path was to tell the truth today, no matter how hurtful.

Had he lived, there might have been other creative periods, as well. A fourth book, a study of homosexuality in the Catholic Church, was in the planning stages at the time of his death.

About the books, Chronicle journalist Mike Weiss said “Although he was only 42 when he died, Shilts’ three books … saved a segment of history from extinction.”

Of his career, Shilts said, “I sort of stumbled into my calling. I found writing comes easy to me. And I like the fun part of being a reporter, that no day is the same, you get to meet a lot of people… it’s a very sociable job.”

Despite enjoying the work, Shilts struggled with an age-old journalistic problem – how to be a neutral reporter, an advocate for change and a keeper of history, all at the same time.

In the quarter century since his death advances in medicine and society have greatly improved the landscape for homosexuals in ways he might not ever have imagined, so his work helped. In the realm of history, though, his work will always be bedrock, not just a recitation of events and transitions.

His journalism was not the journalism in which the intellectual elite explained things to ordinary people. Because of who he was, his reporting came from the realm of the real — the laughter in the bathhouse, the conversations on the street, the whisper on the deathbed. That, and meticulous research and a fiery energy that seemed to never flag.

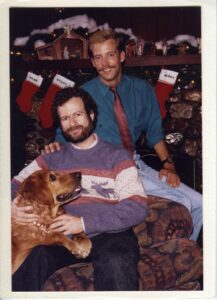

He had several serious romantic partners over time and was formally committed to Barry Barbieri during his last years.

Randy Shilts was a man with a calling, and he gave that his all, employing his charm, intelligence, fearlessness and self-assurance to advance his causes and record for history the tumultuous times of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.

He died of AIDS-related complications in 1994. He is buried near his favorite home in Guerneville, CA.

Who would be surprised that he had kept his HIV diagnosis a secret for years? Back in 1987, when he was writing And The Band Played On, Shilts was tested for AIDS but didn’t want to hear the results lest they influence his objectivity. He told the New York Times later “I literally pulled the last page out of the typewriter and went to the doctor (for the report)”.

After learning he had tested positive, he refused to make the results public so as not to color others’ view of his reporting. He finally revealed his AIDS diagnosis in a 1993 Chronicle article, eight months before his death. He was at work on Conduct Unbecoming until the very end, drifting in and out of consciousness while loyal friends and colleagues pieced together his notes to finish the book.

He was himself the embodiment of what he had said about dying AIDS patients who, just a few years earlier, allowed themselves to be interviewed for And The Band Played On: “If there is an act that better defines heroism, I have not seen it.”

His papers are in the local history section of the San Francisco Public Library. In his hometown of Aurora, his books and a collection of newspaper clippings are kept at the Aurora Public Library District.