By John Jaros

According to the earliest histories, Aurora’s first 4th of July celebration was held in 1837, at a time that Aurora was little more than a hamlet. “The country people came in their ox carts and lumber wagons, and when assembled there were some three hundred persons present,” and “everybody had a good time generally.”

Eleven years later, in 1848, according to newspaper reports, fully 1,000 participants enjoyed a “Great day in Aurora. Great entertainment and then a balloon of large size was sent up, which aroused great admiration. It rose to a great height, could be seen for a half an hour and was finally lost behind a dark cloud.”

Aurora’s celebration in 1854 was significant for being the last statewide assembly of the veterans of the War of 1812, who poured in from all corners. There was even one Revolutionary War veteran in attendance —86—year—old Israel Putnam Warner. Today, Warner’s grave can be seen today at the Big Woods Cemetery on Eola Road.

The year 1876 was the nation’s Centennial, a major celebration, which “was ushered in at Aurora with a tremendous rainstorm, thunder, lightning, the ringing of bells and the firing of cannon.”

The parade, which “was without doubt the most imposing demonstration of the kind ever seen in Aurora,” according to the newsmen, featured bands, military companies, fire companies, and dignitaries, including thirteen of the remaining old settlers of 1835.

Many of the local factories and businesses were represented with wagons featuring their wares or operations: The Daily News with “a whole printing office in operation;” Solfisburg’s Brickworks with “a gang of men making bricks;” and “the Aurora Brewery making beer, the men on the wagon drinking it a little faster than they made it.”

The most impressive feature was a wagon “beautifully trimmed and covered in American flags,” drawn by thirteen horses representing the thirteen original states, and carrying thirty-eight young ladies, each representing a state of the Union in 1876.

The parade wound from the west side, through the neighborhoods and the downtown to Lincoln (now McCarty) Park. Activities at the park included band music, lengthy oratory, songs by the 700-person Aurora Centennial Chorus, and an evening Grand Military Ball under the lights.

Two years later, in 1878, the highlight of the day was the formal dedication of the new Soldier’s Memorial Hall on the Island, construction of which had begun one year earlier. Today, this is the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Memorial Museum, across the street from the Historical Society’s downtown location, the Pierce Art & History Center.

In 1884, Aurora celebrated the semi-centennial of the McCarty Brothers (Aurora’s founders)’1834 arrival with the usual fare of bells, music, and a grand parade. The celebration was somewhat tainted by activities of the previous night, when, according to the Aurora Beacon, “The streets of Aurora were the scene of a riot and confusion disgraceful to the persons engaged in it. Bands of men and boys wandered from end to end of the business streets, throwing explosives [powerful firecrackers] into areas, stores, and open doorways” causing “keepers of saloons, stores, hotels, etc., to close their places of business from sheer fear of being subject to

conflagration.”

In 1890, while “nearly every village, town and city in this part of the state” had a celebration, according to the Aurora Beacon, Aurora did not, “as she celebrated so thoroughly last year that she has not yet recovered.”

Still, the lack of an official celebration that year didn’t prevent smaller celebrations, as “many private citizens exemplified the true spirit of Americanism by giving private displays of fireworks in the evening.” And with that, the newspaper noted, “The usual number of people who ‘didn’t know it was loaded’ immolated themselves upon the altar of their country. …The innocent-looking toy pistol got in some very effective work and the long-tailed firecracker did a good day’s business for the physicians.”

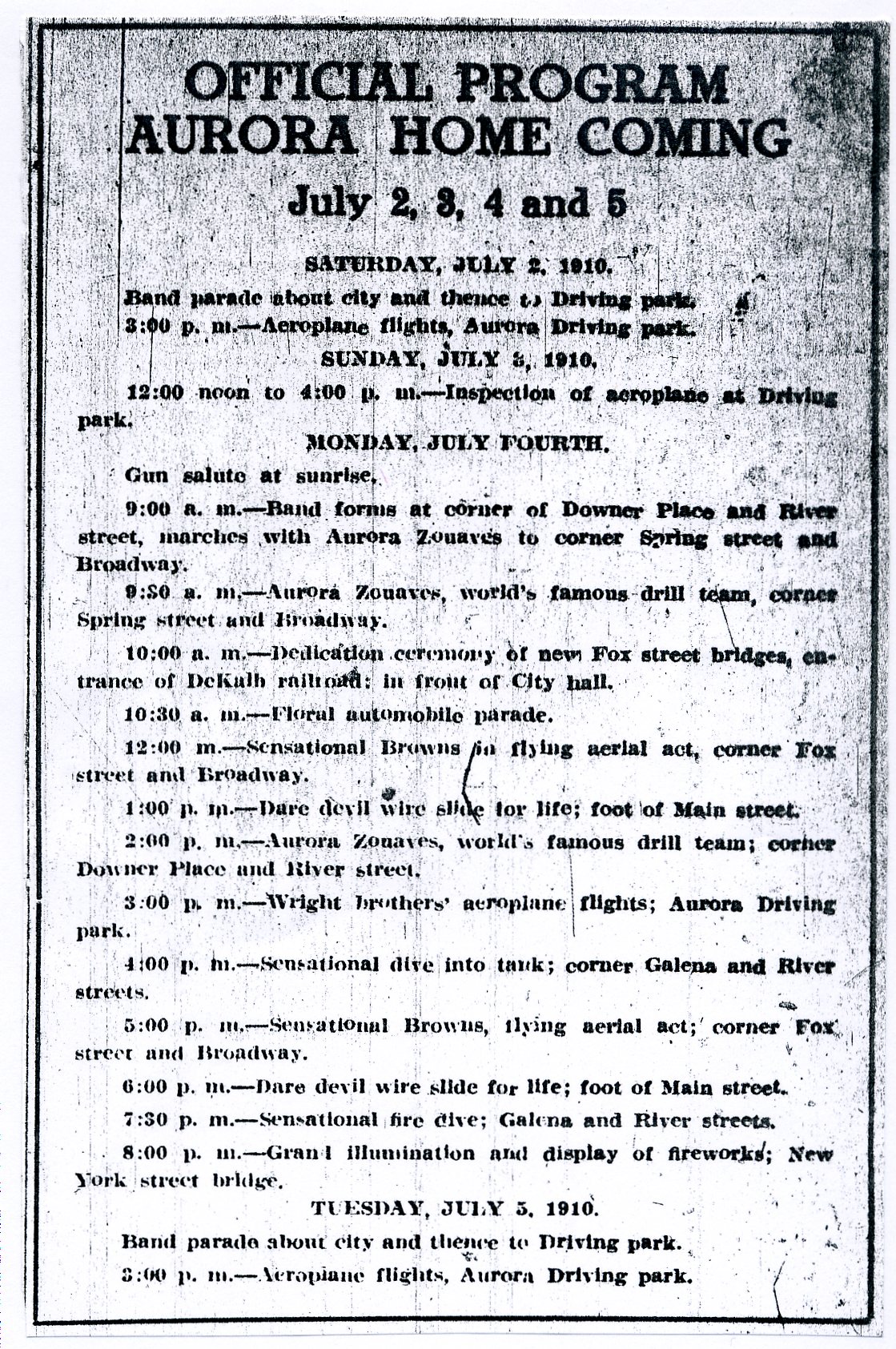

Aurora celebrated many times in subsequent years, but was 1910 that is remembered as “Aurora’s Greatest Fourth.” This was the first official city celebration of the 4th in ten years, and organizers wanted to make up for the long gap. This four-day “Homecoming” encouraged former Aurorans to come back home, and nearby residents to become Aurorans for a day. Festivities were to begin on Saturday, July 2nd and run through Tuesday, July 5th.

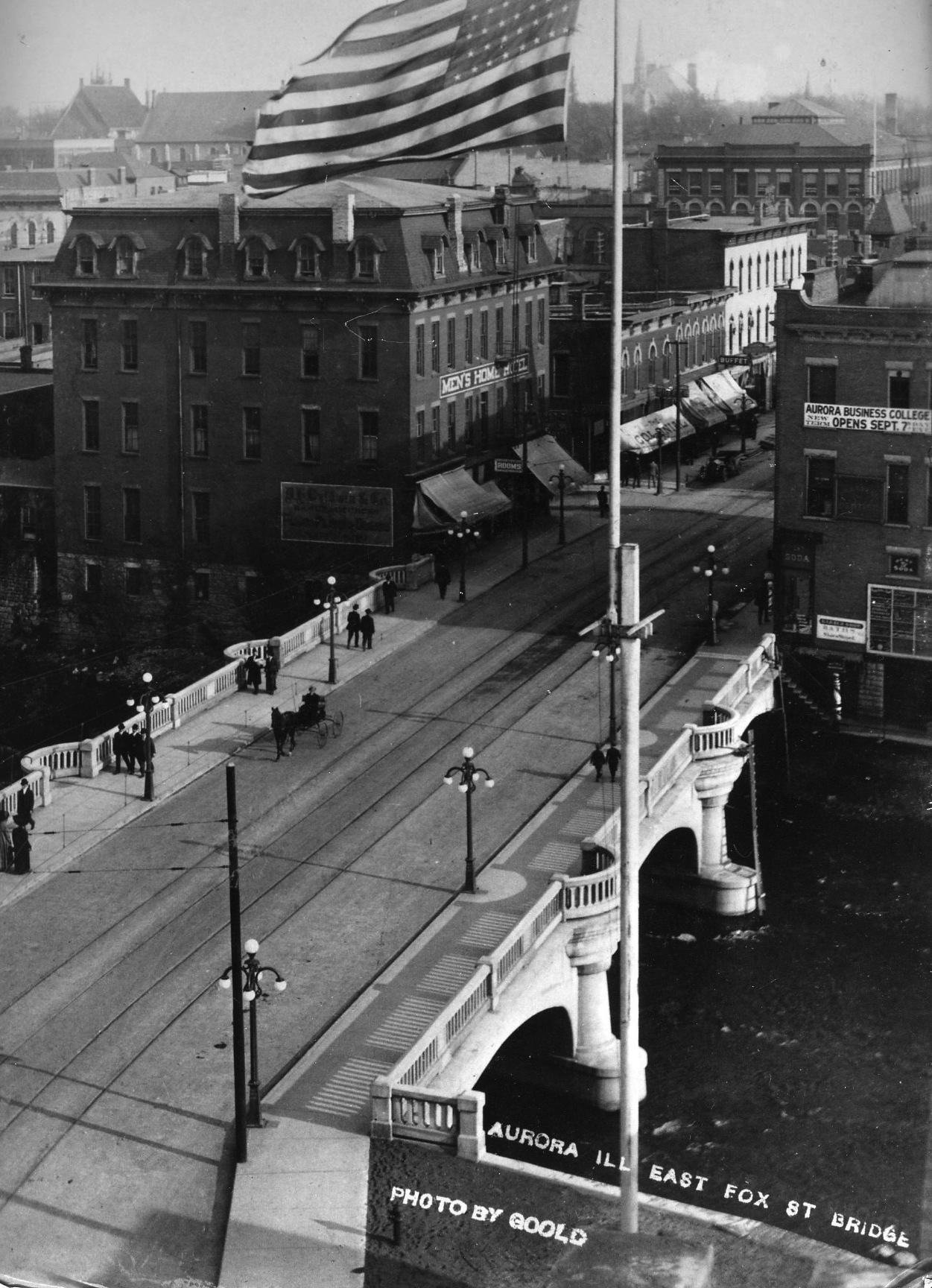

The biggest day was of course the Fourth itself. The streets were “a mass of surging humanity” as an estimated twenty thousand visitors “from every town and city within a radius of 50 miles” joined 30,000 of Aurora’s own. The city’s downtown was splendidly bedecked in flags and bunting. The celebration included the usual patriotic music and marching bands, along with long-winded speeches. It also included the dedication of the new concrete bridges at Fox Street (Downer). This was the dawning of the auto age, and featured a “Floral Auto Parade” with more than 20 decorated autos. A stupendous $1,000 fireworks display capped the evening.

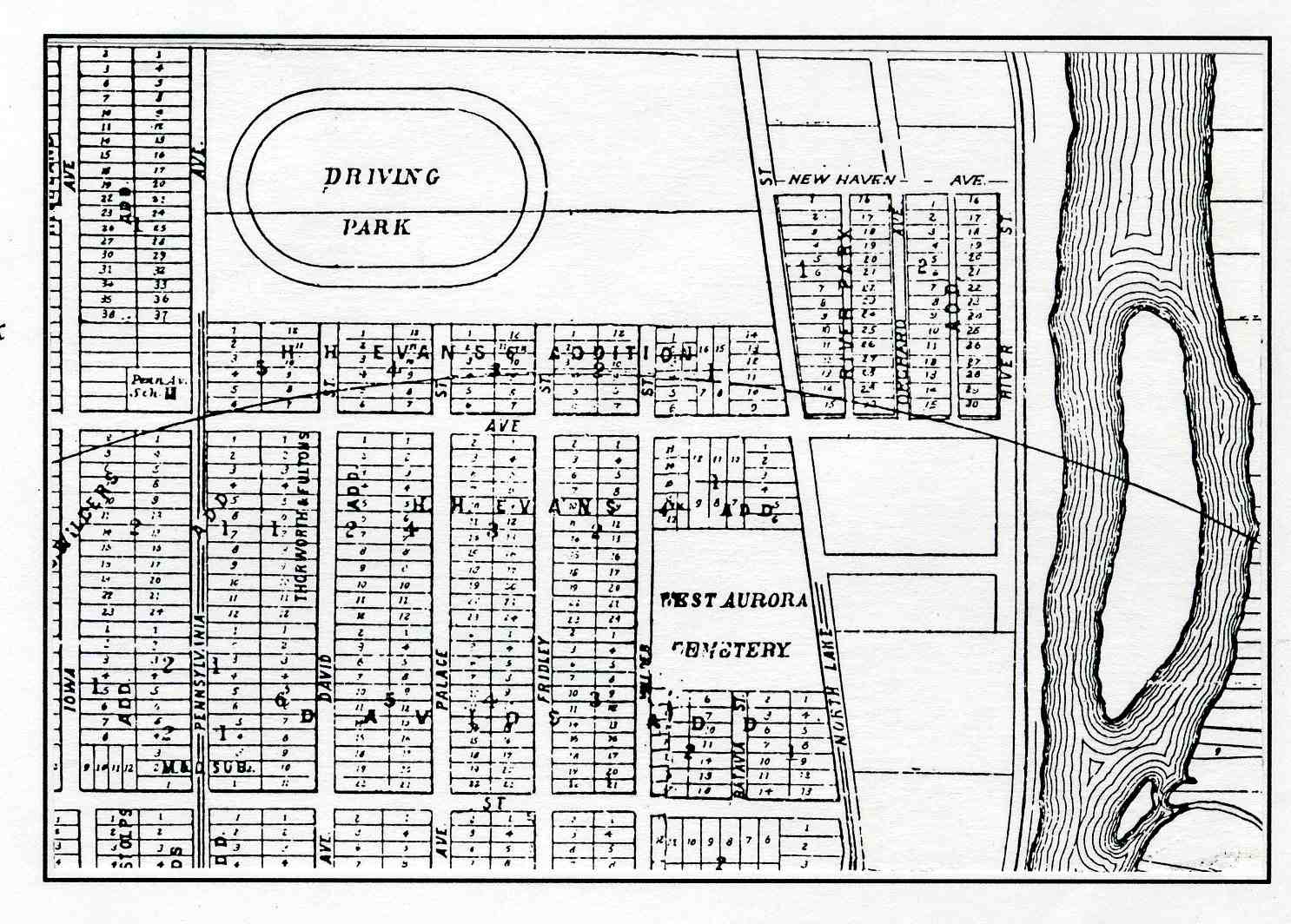

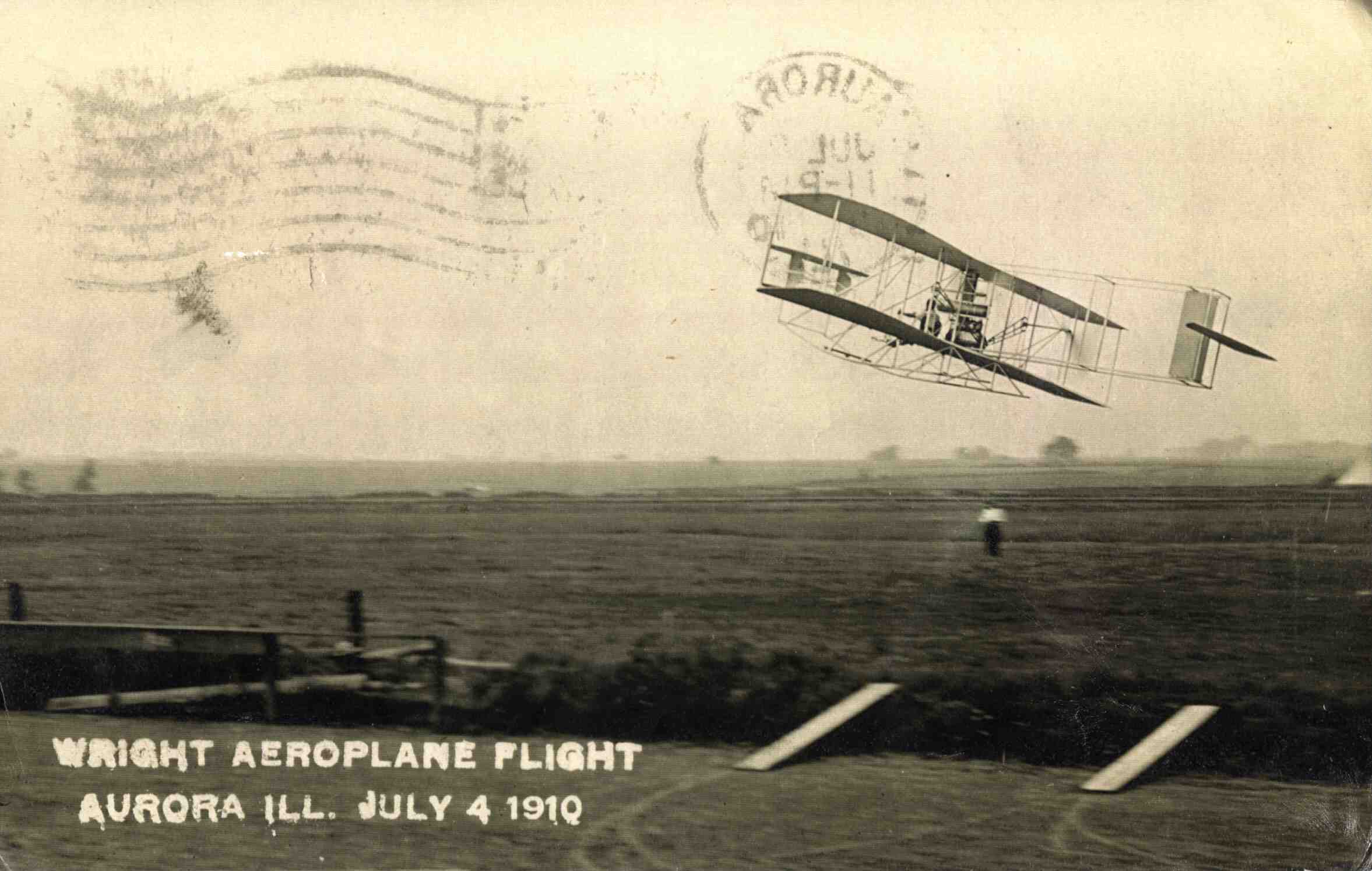

But the premier attraction was flight demonstrations at the Aurora Driving Park—by a Wright Brothers aeroplane–scheduled for every day of the celebration except Sunday July 3. The Driving Park property later became the Riddle Highlands subdivision.

Unfortunately, adverse weather conditions grounded the plane most days. The first day of flights, winds kept the plane on the ground until the late afternoon, when just a short flight was completed.

On Sunday, July 3rd, there were no scheduled flights, yet thousands paid a 50-cent admission just to view the magnificent machine on the ground.

Then, on Monday the 4th, the Wrights’ pilots planned a full three hour program. Winds again kept the planes from going up at all, to the great disappointment of the 7,000 who had paid admission to be in the park, and the estimated crowd of 10,000 outside the park.

The next day, the Wright organization released a statement: “With a steady gale blowing all day yesterday until nine o’clock at night it would have been absolutely foolhardy and dangerous to the public to attempt an airship flight.” However, the Wrights promised to “deliver the goods” with two more good flights in Aurora “if we have to stay here for a week to do it.”

On that day, Tuesday, July 5, stormy weather prevented any flights until late in the day, when Wright aviator Frederick Welsh was able to complete a short flight.

Finally, on Thursday, July 7th, weather conditions finally were right. Factory whistles were sounded to alert the populace. Six thousand people rushed out to the Driving Park, where the pilot reached an altitude of 512 feet and stayed airborne for an hour, delighting the crowd and bringing “Aurora’s Greatest Fourth” to a successful conclusion.