In celebration of Black History Month, we present a glimpse of the early days of Aurora’s black community, which dates back over 150 years, to the Civil War era.

By John Jaros, Executive Director, Aurora Historical Society

Prior to the Civil War (1861-1865), only a handful of Black people are documented to have lived in all of Kane County, let alone Aurora. In the 1850s, Tennessee-born David and Illinois-born Julia Demery and their children, a family of free Blacks, resided in Aurora. Like many persons of color, both slave and free, they were “mulattos,” mixed-race individuals. Their last three children were born in Aurora between 1857 and 1862, and members of the Demery family lived here for many decades.

During the Civil War, a small number of freed slaves from Union-held areas in the south also arrived here. By the time of the Illinois State Census of 1865, enumerated on July 3, there were 59 persons of color residing in Aurora, out of a total population of 9,173. Within the first couple of years after the war‘s end, a larger number came. Many of the newly-emancipated started their new lives in the North in a place called “the Barracks,” an ancient frame structure located near Lake and Benton.

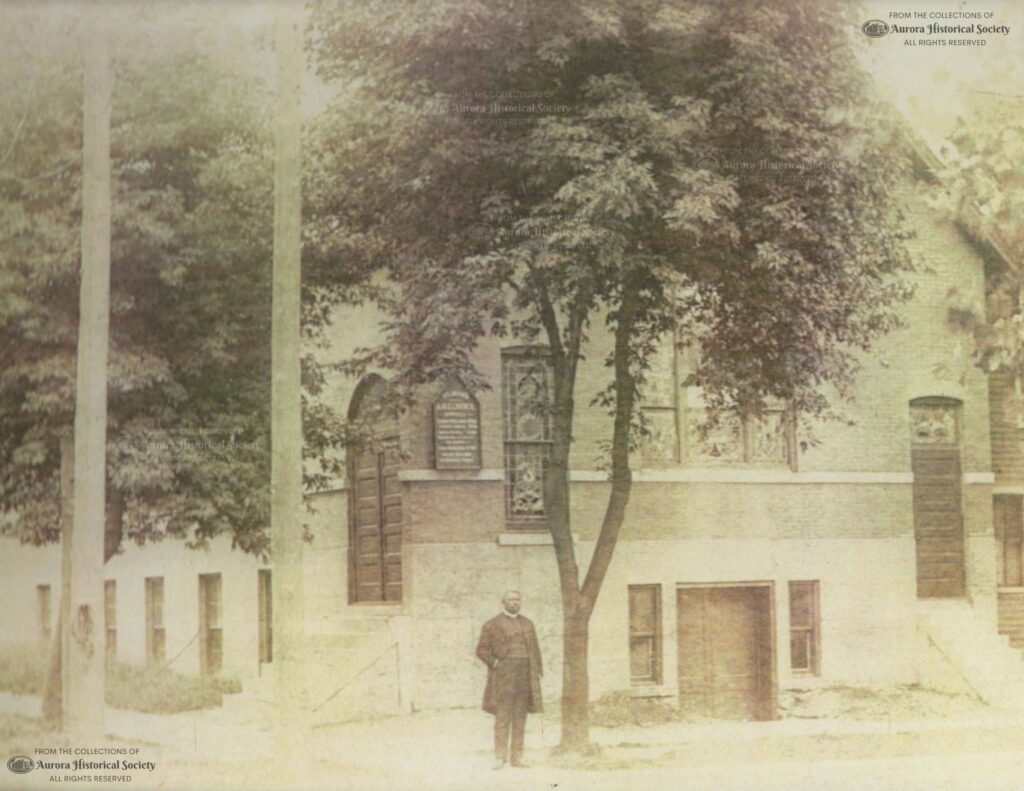

By 1867 Aurora boasted two Black churches — the African Methodist Episcopal Church (today, St. John’s A.M.E.) and the Colored Baptist Church (today Main Baptist). In 1872, Aurora’s black men organized their own Masonic lodge—the Keystone Lodge. And, according to the 1870 Census, Aurora’s black population had grown to 141 individuals identified as “black” and 37 identified as “mulatto” out of 11,162 residents.

The first brick church building of Aurora’s African Methodist Episcopal Church was constructed by contractor Calvin Boger in 1884 (Aurora Historical Society)

From the 1890s to the 1920s what became Main Baptist Church was known as the Third Baptist Church (Photo Collection of Main Baptist Church)

What follows are brief histories of four of Aurora’s many early black pioneers. Starting with very little, they made their livings, raised families, and rose to prominence in the community. Because all were former slaves, details of their lives prior to their Aurora arrival are somewhat lacking.

George Washington Palmer was one of only a handful of Blacks who came to Aurora while the Civil War was still raging. Born into slavery in Tennessee about 1839, he was already married with a young child when he came north, probably in 1862; he is first documented here in a June 1863 enumeration for the draft. George and Mary Palmer’s first child was born in 1861 in Tennessee. Their eight subsequent children, born between 1862 and 1880, were all born in Illinois–in Aurora.

Palmer resided here the rest of his days. He was one of the founding members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and made his living as a teamster. For our 21st-century readers, a “teamster” drove a team of horses, usually hauling wagon-loads of goods or freight. The 1870 and 1880 censuses reveal that both he and wife Mary were illiterate, but by the 1900 census, it was recorded that both were able to read and write. When he died in April 1914, the Beacon called him “one of the oldest and best known colored citizens of Aurora.” He is buried in Spring Lake Cemetery.

Calvin Thomas Boger was among the first former slaves who arrived in Aurora immediately after the Civil War. Calvin was born a slave in Hickory Flat, Georgia–the exact date is uncertain–sometime between 1844 and 1850. In the Summer of 1864, Union troops were storming down from Tennessee, cutting a path of destruction to Atlanta. The fighting came within twenty miles of Hickory Flat, and Calvin ran away to the Union lines.

He came in contact with John Q. Hattery of Aurora, an officer of the 16th Illinois Cavalry. Hattery was a 1st Lieutenant who became Captain during the Atlanta Campaign. Boger stayed with Hattery as an aide for the rest of the war. After the war, he came home with Captain Hattery to Aurora; his first job was in the Hattery Brothers bakery, where he also boarded.

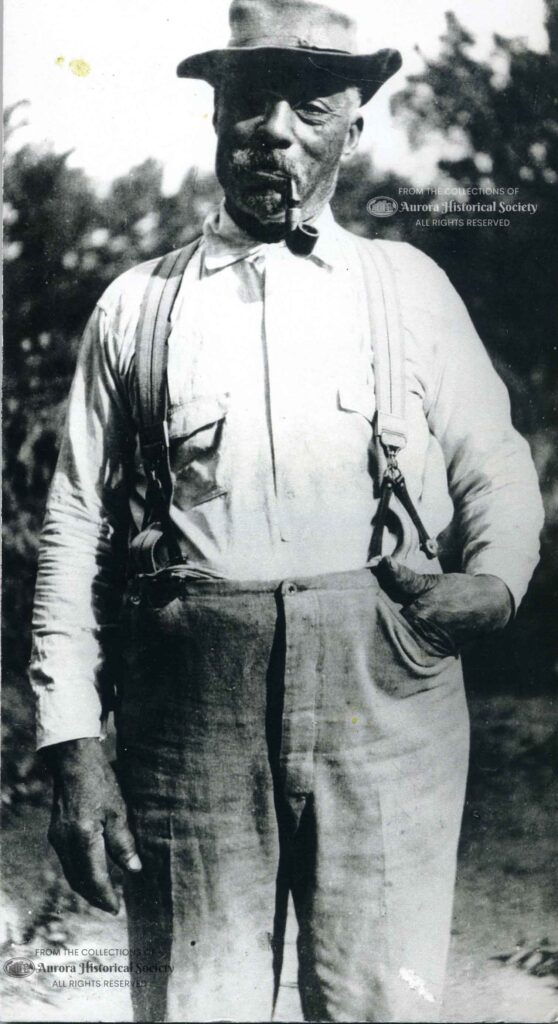

Calvin T. Boger- born a slave in Georgia- came to Aurora immediately after the Civil War (Aurora HIstorical Society Photo)

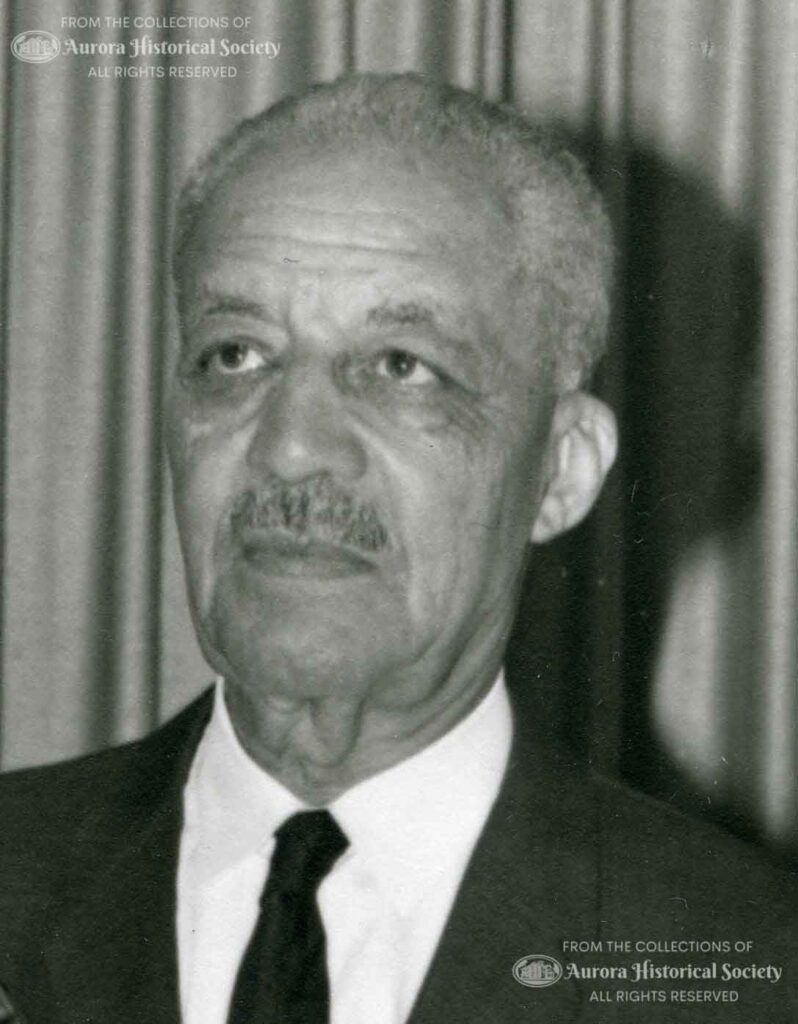

Dr. Thomas Boger (1885-1967) a son of former slave Calvin Boger practiced medicine in Aurora for 50 years (Aurora Historical Society photo)

Henry Hall Boger – born in Aurora in 1887 – was the son of former slave Calvin Boger. Henry was killed in action on the last day of World War I — November 11, 1918 (Aurora Historical Society)

In December 1870, Calvin married 20-year-old Amy Hall of Batavia. Amy’s background was very different from his, having grown up a free Black in the North. Her father was Pennsylvania-born mulatto Abram T. Hall, a very prominent and well-respected minister who made his mark in Chicago, first as a barber, then as a founder of the first African Methodist Episcopal Church there. In 1866, Hall had moved his large family to Batavia.

Calvin learned the plastering and bricklaying trades and prospered. He and Amy raised a family of eight children. One son, Henry, an army officer, was killed fighting in France on the last day of the war–November 11, 1918. Another, Thomas, became a physician and practiced in Aurora for over 50 years.

Calvin Boger died on January 16, 1925, “one the best known colored men in this section of the country,” according to an obituary. He is buried at Spring Lake Cemetery.

Bennett J. Carter arrived in Aurora in the late 1870s. Born about 1850 in Tennessee, little is know of his life before his arrival in Aurora. We know only of his Aurora life: his work as a mason contractor–a familiar trade for black men at the time–and his prominent church work. He was a deacon in the Third Baptist Church, which later became Main Baptist.

In May, 1880, he married Susie Catlett in Aurora. Susie, born in 1863, was one of 11 children born to Catherine and Cornelius Catlett in Clarksville, Tennessee. After her husband’s death, the widow Catherine had moved with a number of her children and grandchildren to Aurora, sometime in the mid- or late 1870s.

Unidentified Aurora ladies photographed by Casimir Arcouet –1890s (Aurora Historical Society)

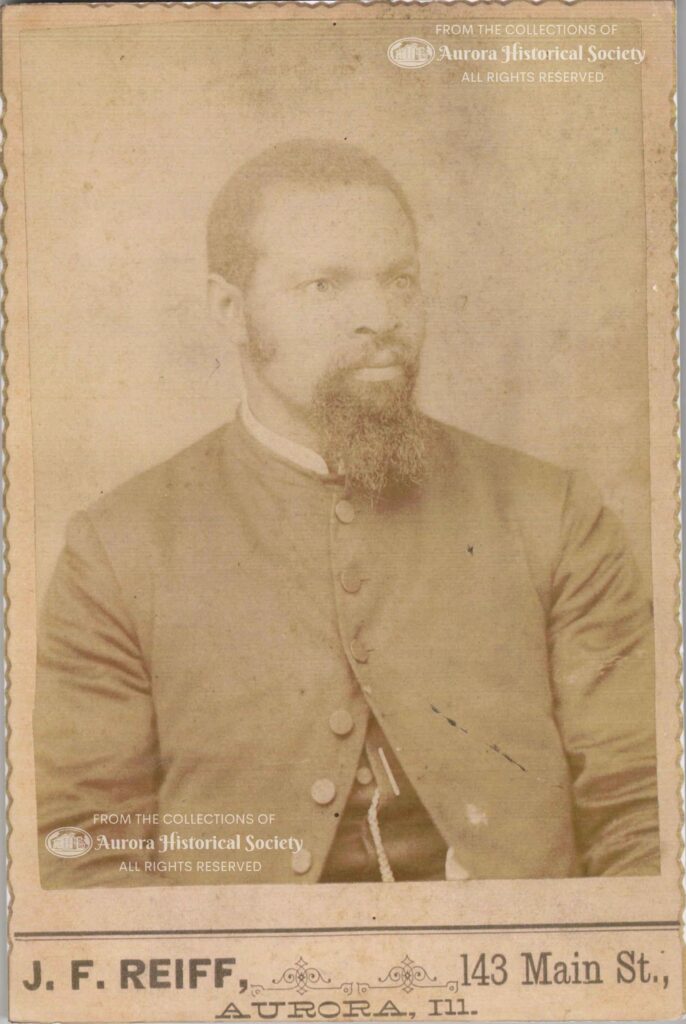

Unidentified Black gentleman from Aurora – photographed by J.F. Reiff – 1890s (Aurora Historical Society)

Decades later, when Ben Carter died in August 1908, leaving his widow and eight living children, the newspaper hailed “Deacon” Carter, as he was familiarly known, as “one of Aurora’s best known and most highly respected colored citizens.” He is buried in West Aurora Cemetery.

One of his children, Isaiah “Ike” Carter, born in 1885, took over his father’s plastering business, and also became a respected deacon in the church. Ike lived to the incredible age of 106 years, dying in June 1991.

Alfred C. Lucas was born somewhere in Kentucky about August, 1857, and first appears in Aurora documents in the mid-1880s. Little is known of him prior to that time. Census documents from 1900 indicate that he was able to read and write, so he’d had some education. In February 1886, Lucas was united in marriage to Mary “Emma” Carter in Aurora.

Emma, born in Aurora in May 1866, was a daughter of Henry W. Carter (no relation to Bennett Carter), a former slave and early Black pioneer in Aurora. Her father died when she was a child, and her mother, Lucy, remarried in 1877 to Perry Brooks. Brooks, born in 1837 in Kentucky, was another prominent black pioneer in Aurora, and a founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Alfred and Emma Lucas had just one child that lived to adulthood, Pearl, born in 1890. But Alfred left his mark in other ways. About 1890, he became the patrol driver for the Aurora Police Department. For sixteen years, until his untimely death in 1906, Lucas held this important position. The horse drawn patrol wagon, known commonly as “The Black Mariah,“ served as paddy wagon, ambulance, and hearse. It was called in to transport the sick and injured to their homes or to hospital, to transport dead bodies, and to assist on the vast majority of arrests, transporting arrestees to jail. In 1903, for instance, Lucas and the patrol wagon made approximately 800 such runs. Through this, said an article at the time of his death, “there is perhaps no other colored citizen of Aurora who is so widely known,” his position as patrol driver having “continuously kept him in the lime light.”

A member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church during his lifetime, Lucas lies resting in West Aurora Cemetery.