By John Jaros, Executive Director, Aurora Historical Society

140 years ago – on November 8, 1881, Aurora became one of the first cities in the country to light its streets with electricity. This is the story of how that came to be.

In our modern world, with its over-abundance of outdoor artificial lighting, it is difficult for us to imagine just how dark (and dangerous) nights could be, even in the centers of busy towns and cities more than a century ago.

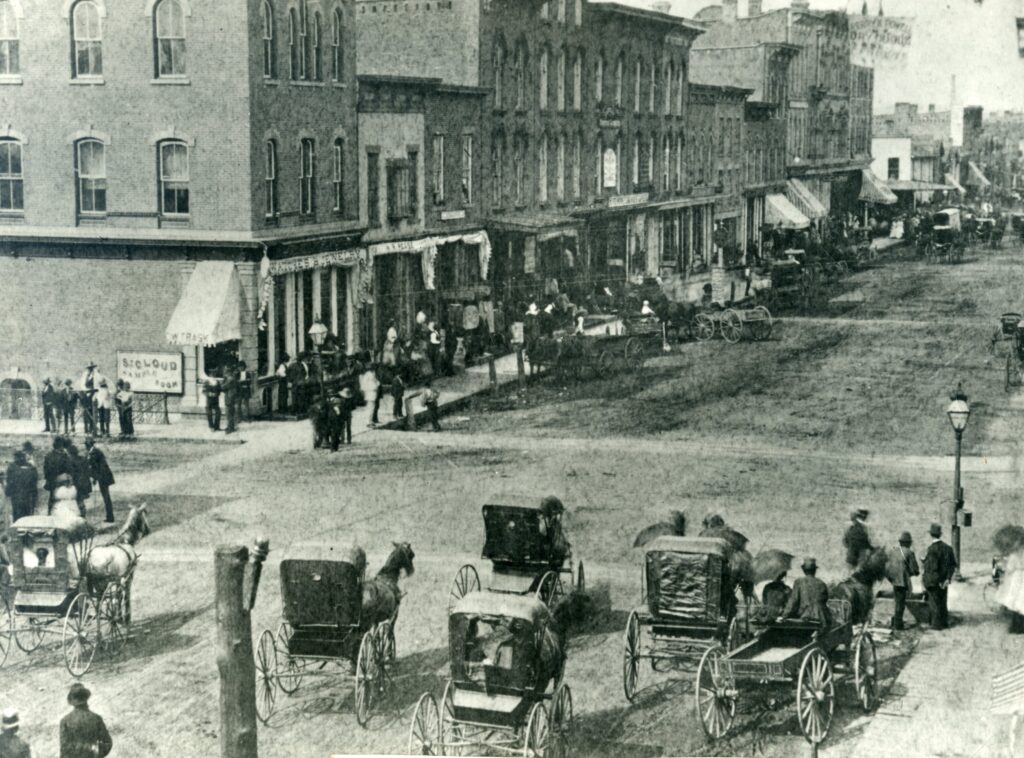

In the 19th century, gas lighting developed as the solution for fighting the darkness, both outdoors and inside homes and businesses. Weak by today’s standards, it had a yellow hue and was not very bright, but it was the best thing available at the time. This was not the natural gas that we know today, but “coal gas,” manufactured by heating coal. Filtered, pressurized, and stored in huge tanks, it was distributed to streetlights and homes via underground pipes going to various sections of town.

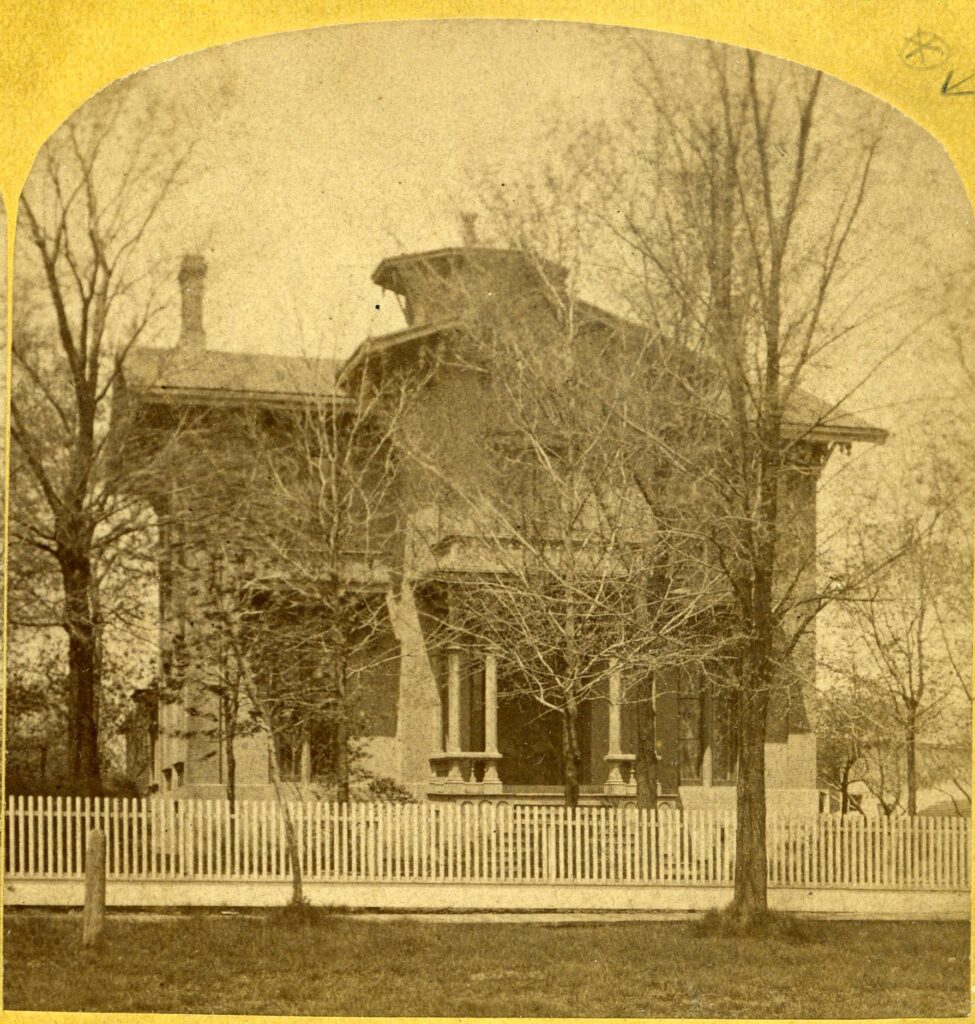

The first American city to light its streets by gas was Baltimore in 1816, and by the 1840s, most cities in the East had gas streetlights. In the Midwest, Chicago had to wait until 1850, and by this time, gas lighting was entering homes and shops as well. Once Chicago got gas, it was just a matter of time before Aurora would follow. In anticipation, in 1857–years before Aurora established gas service–local merchant William A. Tanner had gas piping installed in the new house he was building on Aurora’s near west side.

The city was just getting its start with the formation of a gas company in 1861 when the Civil War intervened, delaying construction until 1867. Finally, on December 24, 1868, Aurora’s gas streetlights were turned on, replacing kerosene lamps on wooden posts that had previously lighted the streets.

The decorative metal gaslights were topped with square-sided glass enclosures for the lamp. The poles were installed at street corners, covering the center of the city. But people in the far reaches of the city derived no benefit, as the gas posts were not installed far beyond the downtown business district and closely surrounding residential areas. Indeed, by 1880, it was said that only one-fifth of the city was lighted.

The gas lights continued to do their job until 1881, when the multi-year gas contract expired, and the City Council was unable to come to a new agreement with the gas company. Starting on February 22, Aurora’s streets would be in darkness for several months while the City Council explored and debated their options. Electric lighting came into serious consideration.

The incandescent light functions by heating up a filament, producing “incandescence” –light produced by heat. Thomas A. Edison did not invent, but perfected, the incandescent light bulb in late October 1879 after he and his team of researchers spent 14 months and performed 1,200 experiments to get it right. But it was not until September 1882 that Edison perfected a complete municipal lighting system, lighting a square mile of Manhattan.

Another early form of electrical lighting was the arc lamp. This type of light used two carbon rods placed closely together to generate an electrical current between them (powered by an outside source—a battery, and later, massive power-generating dynamos). The current between the two rods would create a bright, glowing arch, or arc. This method was known and experimented with since 1807 in Europe, and improved by the 1870s.

Charles H. Brush of Cleveland, Ohio, did not invent the arc light, but, like Edison with the incandescent light, he was the man who perfected it—making it simpler, more reliable, and cheaper to operate. Brush developed a better arc light, a better dynamo to power it, and worked out the intricacies of running lines to the individual lights.

As opposed to the warm yellow glow of gaslight, arc lights gave off a harsh white light, too powerful and bright to be close to the ground, hence Brush placed them up high, often on tall towers, about 150 feet from the ground.

Brush and his system were proven commodities. The first major public demonstration of the system had occurred in his hometown of Cleveland, when on April 29, 1879, he lighted a downtown public square with twelve arc lights. On March 31, 1880, he lighted an entire town with his lights. Wabash, Indiana, was a tiny town of just 500 souls, so Brush was able to light the town with a cluster of four 3,000-candle power arc lights placed atop the new Wabash County Courthouse.

Center School with light tower, 1895 (Aurora Historical Society Photo)

Young School with arc lights, 1886 (Aurora Historical Society Photo)

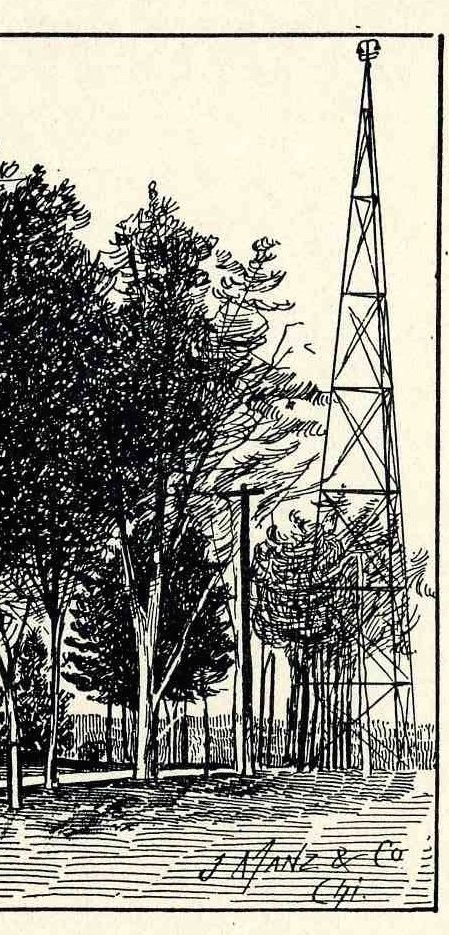

View showing the base of a lighting tower on the grounds of Jennings Seminary, Broadway & North Avenue, 1900 (Aurora Historical Society Photo)

Brady School with arc light tower, 1886 (Aurora Historical Society Photo)

On December 20, 1880, Brush lit twelve blocks of Broadway in New York City with his arc lights, creating a “Great White Way.” Later, in August 1882, he would light the City of Detroit with seventy arc light towers, soon expanding to 122 towers and illuminating 21 square miles.

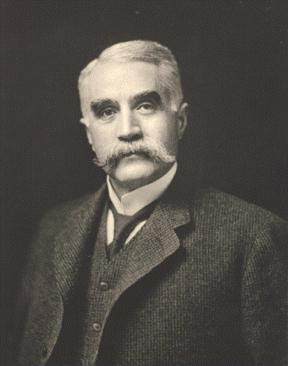

In the meantime, in the Spring of 1881, Aurora was still without street lighting. Some of the aldermen were strong proponents of the idea of electrical lighting, and won the others over. Alderman L. O. Hill, owner of a sash factory, obtained a franchise from the Brush company, and formed the Aurora Electric Light and Power Company. The city would contract with Hill to bring the Brush “several tower” lighting system, complete with power plant, for a 5-year period. The City council approved the plan and contract in late April, 1881, but it was several more months before the plant, wiring, and towers were completed.

Initially, there were to be 16 arc lamps, with an option to add more. Each lamp was 2,000 candle power – equal to the light of 125 gas jets. These were placed on seven strategically-located 150-foot towers, with each tower holding two or three of these powerful lamps. The original arrangement placed four towers on the east side, two on the west side, and one in the downtown center on Stolp Island. Built of iron pipe, some towers were free-standing from the ground up, but if a tall building with a bell tower was available (such as a school), a smaller light tower was placed atop that. With this “several tower” system, Aurora was able to theoretically light the whole city with electricity, rather than just one-fifth of it with gas. Aurora boasted it was “the first city in the entire west to adopt the electric light.”

The whole system was finally in place and first started up on the evening of November 8, 1881. The next day, the Aurora Beacon sent out a roving reporter to gauge people’s reactions to the new light. Some opined that the arc towers lighted the sky better than the ground, but for the most part, the reactions were overwhelmingly positive. And it was certainly an improvement over the gas streetlights.

Put Howard related, “I walked up and down Lake street and could see very plainly.” General A. F. Wade noted that “In my neighborhood, North Root street, it was very light. Much more than the gas ever gave us.” Many compared the light to bright moonlight, but W.H. Watson went a step further, reporting, “I was near Lincoln park when the light was turned on and the park was as light as day.”

The reporter was unable to reach W.A. Tanner, well-known hardware merchant who resided in a grand residence on the west side. “The reporter did not see Mr. Tanner, but learned that even he was pleased with the light.” This was perhaps due to his home being located just blocks from one of the towers.

Even those in the far reaches of town were pleased. John W. Kendall, residing “at the extreme end of Main street,” three-quarters mile from the nearest light, reported, “I could tell the time by looking at my watch while standing on the front porch of my residence, and when I went to get into my wagon in front of the house I could plainly see every buckle on the harness. I think it is grand.” W.V. Plum agreed: “At my home on North Lake street, where it has been dark for centuries, the light shone very plainly. We who have lived out beyond where the gas posts used to be now have something for the taxes we pay for lighting the streets.”

And the lights atop their high towers could be seen from miles away, attracting great interest. “Frank Belden, who lives at Kaneville, 15 miles away, says that he can see the light from his place.”

By the contract, the lights would operate from dusk until midnight, 288 nights nights a year, plus 12 nights additionally if needed. On nights when there was enough moonlight, the tower lights were not lit, for they were only meant to mimic strong moonlight. In many communities such lighting towers came to be called “Moonlight Towers.”

In succeeding weeks and months, delegations from other towns came to investigate the revolutionary new light. In May 1882, a visiting team from Fond du Loc, Wisconsin reported back to their city that “the light was found to be sufficient everywhere to be a substantial aid to the pedestrian,” concluding, “electric light is a success.” In the space of a couple of years, towns large and small were adopting electric arc lights for streetlighting, most using the Brush system; it is estimated that the Brush Electric Company was supplying 80% of the arc lighting gear in the U.S.

As Aurora’s original light contract was expiring in the fall of 1886, Aurora became the first major city to own and operate its own electric plant, purchased from the Thompson-Houston Electric Company, a rival of Brush. Thompson-Houston installed two dynamos, a boiler, and a new 20-mile copper wire circuit for the 26 arc lights, each of 2,000 candle-power. By 1889, that number had grown to 81 lights “suspended in all parts of the city, many of them on high towers,” according to an 1890 account.

By that time, there were also two private electric lighting companies operating in town. One was supplying about 100 arc lights. The other was supplying the new incandescent lights, about 1,000 in number. At that time, and for some time afterward, the insides of most homes and many shops were still lit by gas, and there were two local gas companies to supply that demand.

By the turn of the new century, Aurora’s original light towers were nearly twenty years old and the worse for wear – rusting, leaning, and deemed to be generally unsafe. In late January 1902, the towers were demolished, although it seems that the tower atop Center School remained for several years more.

Free-standing light tower at Garfield & View, shown 1890 (Aurora Historical Society Photo)

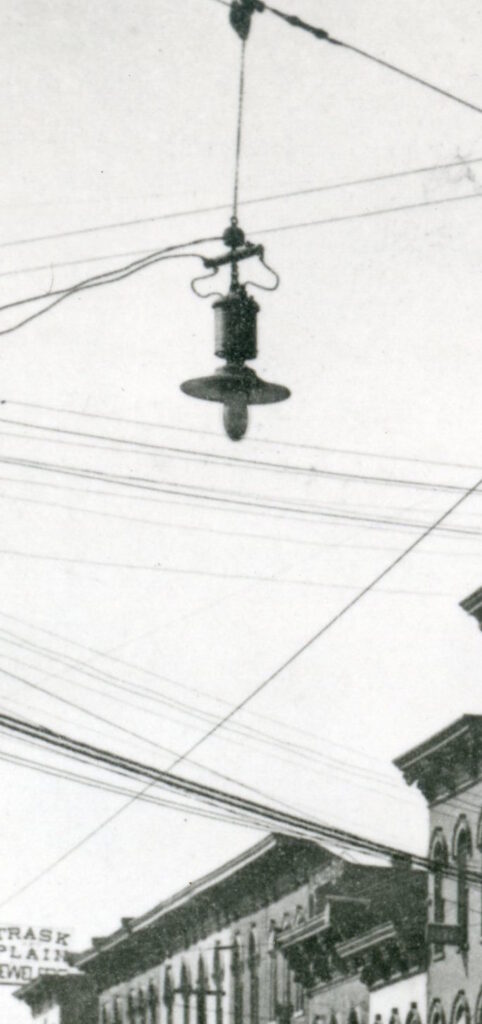

Closeup of light suspended above intersection of Main (Galena) & Broadway, c. 1910 (Aurora Historical Society Photo)

The year 1907 saw a complete upgrade of Aurora’s municipal electrical plant and system, and by that time, over 400 street lamps were in operation in the city. Most had come down to earth—often suspended on wires across streets and intersections about 15 to 20 feet above street level.

At that point, Aurora was on the verge of a great change. In August, 1908, merchants on River Street banded together as the West Side Improvement Association and formulated a unique new street lighting plan that would beautify the downtown area, attract more business, and identify Aurora as truly “The City of Lights.”