By John Jaros, Executive Director; and Mary Clark Ormond, President, Aurora Historical Society

This holiday season, as you pop one of those stylish new ice globes into your favorite drink, or chill that champagne in an ice bucket, spare a thought for the history of ice in the home. Because ice was not always just magically there when you opened your freezer door. In fact, while you might have had, in the 1800s and early 1900s, an icebox in your pantry or lean-to to keep your meat and dairy fresher, how the frozen stuff got in there was a long, cold story that could have taken an entire year to unfold and involved plenty of human and equine muscle, wicked-looking hand saws, conveyor belts, wagons, mountains of straw, and an awful lot of cold feet. And cold hooves, too.

In the 19th century, supplying ice was a big business all over the U.S., and nowhere more so than in Aurora, Illinois, where a fine river and a large urban population combined to create a flourishing market. One of many local ice companies, although certainly not the first, was founded in 1869 by German immigrant Fred. Schaub and under John Kinley’s later ownership grew to an impressive operation at the foot of Cedar Street able to store several thousand tons of ice and distribute it year-round using a fleet of 4 wagons.

Ice was no more and no less than a winter crop in Aurora. The harvest provided welcome employment for local farmers and laborers, despite the discomforts of the weather and the constant risk of man or beast falling into the water. Although it required no sowing, it was as subject to the vagaries of the weather as any summer crop and two successive years of good ice was considered a fortunate run of luck.

In a cold winter the Fox might freeze to well over two feet thick and even in milder winters the ice would be several inches thick. An ideal season created 12-16 inches of ice depth, strong enough to support the necessary teams of horses and men.

The first step in ice harvesting was to use a horse-drawn scraper to remove any snow. Dimensions were calculated and heated augers were sunk into the ice to mark out the field. Then, using an ice plow and skills perfected during spring crop planting, long straight rows were scored in a few inches deep, followed by perpendicular scoring to create a grid pattern. The blocks defined in this way would then be cut by hand using a special long ice saw. The blocks, weighing approximately 200 pounds apiece, could then be maneuvered by picks into a channel of open water and floated along to a ramp or conveyor belt and muscled into a storehouse and covered with multiple layers of hay, sawdust or other material that did not conduct heat from the earth or the air. Although this retarded melting, it did little ensure the sanitariness of the product. The proximity of hardworking horses further complicated efforts at cleanliness and special workers were assigned to attend to the ground conditions.

Although much of the Fox River ice was loaded into box cars and sent to Chicago, some was kept local, stored in long, low wooden ice houses near the river. Ice that was well-stacked and packed could last for up to two years. Thus, even throughout the warmer months Aurorans were assured of a steady supply of ice, brought to them by the ice company of their choice. Deliveries began early in the morning when the ice man would load up his wagon with blocks of ice and drive his route about town, peering at signs in kitchen windows to learn how much ice was wanted that day. Working from the back of his wagon he would chip off smaller blocks, perhaps 25 or 50 pounds each, and carry them, using heavy tongs, straight to the homeowner’s ice box.

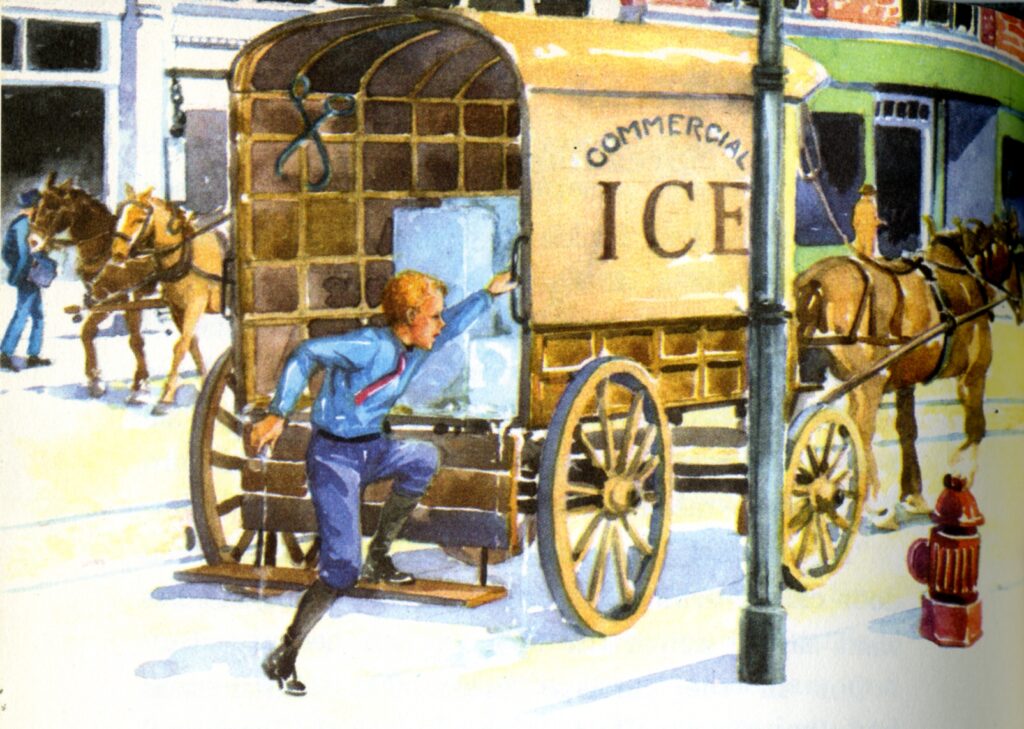

There is a charming glimpse of the ice business in a schoolbook by Aurora teacher and author Mabel O’Donnell. One of her Alice and Jerry progressive readers, beautifully illustrated by the sisters Florence and Margaret Hoopes of Philadelphia, includes a summer scene in which a boy jumps on the back of an ice wagon to refresh himself with ice chips. Since O’Donnell’s fictional town of Hastings Mills is entirely a thinly-disguised Aurora, the *Commercial Ice Company* in the book Engine Whistles is almost certainly the real-life Consumer Ice Company once located at 161 S. View St.

Inexorably the advent of electric refrigeration eliminated the need for river ice and delivery wagons, and our second harvest, winter ice, became a thing of the past which we merely wonder at today.

This holiday, when you hear the tinkle of ice cubes, raise your glass to the intrepid folks who used to cut ice on the Fox River. Don’t let their memories just melt away.