This post originally appeared on Kane County Connects

Precisely at the midpoint of the 1800s, William and Anna Tanner packed up their household goods and growing family and moved from their farm on Deerpath Road to the city of Aurora.

At the very same time, an aspiring artist in Massachusetts named John Rogers (1829-1904) began mass-producing affordable sculptures intended to decorate the homes of middle-class Victorians.

We have no evidence that the Tanners ever purchased a Rogers statuary group to decorate the impressive house they built for themselves in 1857, although they certainly might have.

Victorian standards of décor called for homeowners of taste to pack their parlors to the brim with every type of object imaginable. Sofas, chairs, tables, pianos, photos, paintings, lamps, sconces, vases, clocks, plants, scarves and gewgaws aplenty were employed to fill the room and cover available flat spaces.

To have a bare mantel and plenty of room to maneuver around the parlor was to display a lack of good taste and even a certain sort of moral failing, placing you outside the bounds of social conformity.

So we have no evidence of a Rogers group at 304 Oak Ave. while the Tanners lived there, and yet the Aurora Historical Society has traditionally displayed in the house the 24-inch-high “Council of War”, one of the most familiar of the Rogers groups.

How, then, did the AHS come to possess this piece?

Records don’t show, but it has apparently been with us since the very earliest days of our ownership of the house, meaning the middle 1930s. After the death of Henry Tanner, a bachelor and the last of the family to occupy the house, the twins Mary Tanner Hopkins and Martha Tanner Thornton donated the house to the Aurora Historical Society with the understanding that first the family could claim whatever effects they wanted.

The result was a pretty bare house, with only a few extra-large pieces like the square piano and the towering pier glass (mirror) in the parlor remaining. (It is tempting to think that none of the children had big enough houses of their own to accommodate them.)

Before the society could open the house to visitors, it needed to be furnished, and kind Aurorans pitched in with Victorian items from their own attics and barns. It was then, we conjecture, that “Council of War” came to stay.

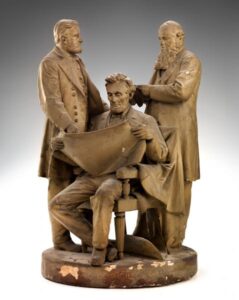

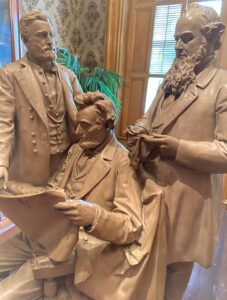

The sculpture features, as Executive Director John Jaros always says, “a meeting that never happened except in the mind of John Rogers.” It shows a seated Abraham Lincoln, flanked by General Ulysses S. Grant and Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. Lincoln is examining a map, with Stanton looking over his shoulder while Grant makes some tactical point.

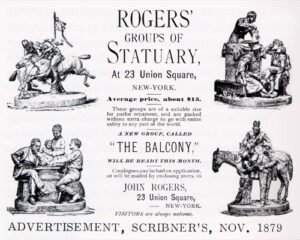

The statue nicely illustrates John Rogers’ business model, which was to create all-American images that would appeal to a broad swath of customers, and mass produce them in plaster, which would put them at a price point attractive to the middle class.

Abraham Lincoln was highly revered in the North and a very popular subject for artwork and literature. We do know the Tanners were great admirers of Lincoln and that they liked nice things. It is no stretch to think that they might have owned a copy of “Council of War”.

In the 1860s-’80s, these sculptural groups sold for around $14 each, depending on size. Had they been sculpted in marble or cast in bronze, they would have been true fine art and cost hundreds of dollars at the time. Today these plaster pieces are represented in museums around the country and, needless to say, have appreciated enormously in value.

Roger’s technique was to model in clay, then cast in bronze, from which plaster copies would be created. Over his career, he created 80 groups. They were reproduced by a staff of as many as 25 workers in his New York factory and were finished in various monotone colors, although occasionally painted in full color. The historical society statue is putty color.

The rise of the middle class in the Victorian era created a demand for the illusion of gentility. Items made of silverplate, meant to lend luster to a table where sterling silver could not be afforded, or plaster that at first glance might be marble, were very much in vogue.

Artistically, John Rogers was a chronicler of American life in the same way that Currier and Ives and Norman Rockwell were. His Lincoln and George Washington sculptures were the only formal depictions of celebrities he made.

Mostly his work was informal, full of emotion and warmth, depicting homey scenes, often with children. Even his Civil War-themed pieces were highly personalized studies of individuals in wartime settings.

Rogers was also attuned to his customers. The first release of “Council of War” had Stanton positioned so his hands and eyeglasses were directly behind Lincoln’s head, a position that suggested to a traumatized public that he could be holding a gun to Lincoln’s head. Rogers quickly re-sculpted the group, rotating Stanton slightly so that his hands are in full view, harmlessly polishing those glasses. That is the version that the historical society has.

Rogers groups were ubiquitous in middle-class America during the late Victorian period. For homeowners, it was almost de rigeur to have one if you wanted to appear cultured and tasteful. If you had a bay window in your house, you could really show off because the statues were made to be seen from all angles.

Scarcely a bookstore existed that did not have at least one for sale in the shop window. “Council of War” was most likely one of them.

In the past few years, the Historical Society has displayed its copy of “Council of War” in the library of the Tanner House, a room where several period engravings of Abraham Lincoln and his family also hang. In the summer of 2021 the sculpture was temporarily relocated to the Pierce Art and History Center in downtown Aurora so it could be included in the post-pandemic reopening exhibit, “Our Favorite Things”.